(a condensed history)

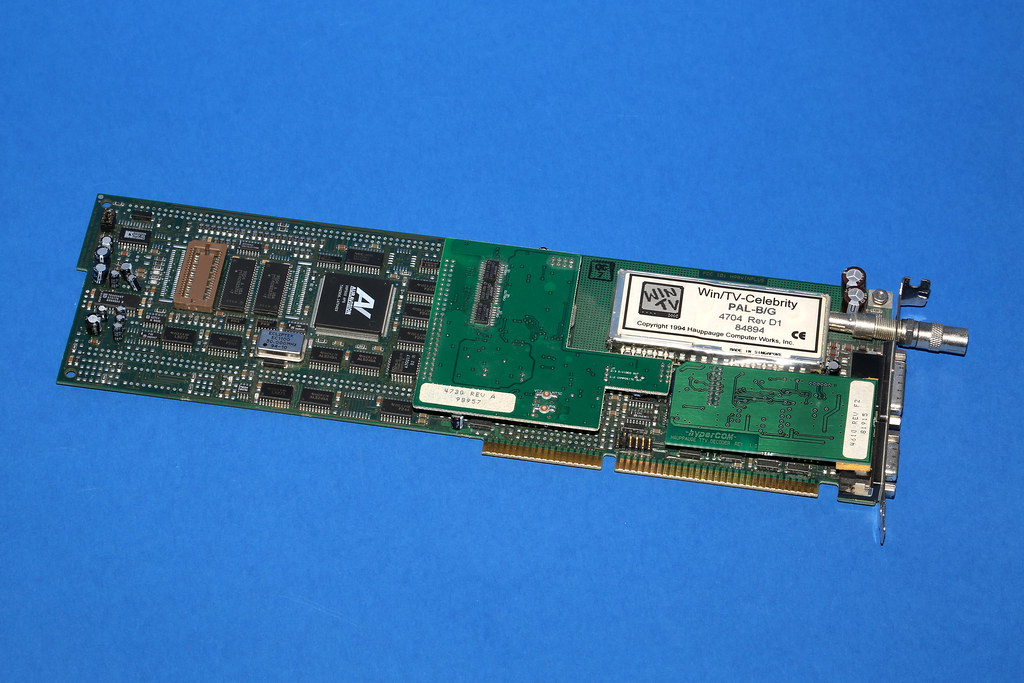

Way back before the statute of limitations expired, I very much enjoyed using my Hauppauge WinTV to convert analog to digital and did a lot of sharing of things with friends. I found it fascinating that an (ISA) card could convert the analog TV signal to a digital format. That the output was a literal digital copy of the input source (wavy tracking lines and all) was surreal. If you grew up with lossless everything, this probably sounds quaint. I grew up when most consumer media had a laughably short half-life. Play a vinyl record hard for a year and it starts to sound like sandpaper; no parity volumes, no checksums. Cassettes shed ferric oxide like a nervous cat or got eaten by a cranky pinch roller. Get a tape near a magnet? RIP. Same story for “digital” tapes, and, of course, floppies and other magnetic ephemera. Transcoding was an archivist’s fever dream.

Technical challenges for media on the early internet

One of my first jobs was at Time Warner/Road Runner, building “value-added services.” VOD was just rolling out. Real-time transcoding wasn’t a thing you casually did in software; you did encoding offline. Master tapes and hard drives were shipped to ingestion, encoded to MPEG-2, and then staged on on-demand servers. From there the streams went out through edge gear and QAM to set-tops for playback. Sidecar files rode along: metadata, captions, language tracks, markers, and trick-files (I-frame indexes so fast-forward didn’t look like a blender).

Around ~2000, 56K modems (yeah, 53.333333333 for the pedants) were still everywhere. Cable and satellite internet were showing up, but most people were not streaming anything you’d call “good.” Outside of very low-bitrate stuff (hello, .rm/.ram), “streaming” meant you were rich or you worked at an ISP. Meanwhile, the gray-to-black market moved fast: video codecs were being cobbled together and optimized at a dead sprint—basically the video rerun of the audio scene (Napster, CDDA rips, and the absence of copy protection on CDs >>’d this).

The need for transcoding explodes

By ~2002, most ingredients were on the shelf. For audio, the center of gravity had shifted to MP3; for video, DivX (yes, DivX 😉) was the popular hack, itself a French side-eye to that brief Circuit City DIVX format that lived ~82 milliseconds. Transcoding jumped from geek trick to “required step.” You couldn’t assume a source matched your target device, bit-rate, or container. If you wanted reach, you transcoded.

Infrastructure grows up just enough

By ~2003, the app-layer pieces and most of the transport story were basically there. RTP/RTSP had real RFCs; that other big streaming workhorse of the era did not have an RFC but was everywhere anyway. Broadband reached enough households that real businesses could justify building out storage, ingest, and early CDNs. The core of the internet wasn’t ready for hundreds of thousands of concurrent video sessions on day one, but caches, peering, and edge distribution caught up quickly because demand forced the issue.

YouTube (and why transcoding became the main character)

I’m skipping detail on purpose because all time is valuable time.

Short version: YouTube lit the fuse. It launched in 2005 and got bought ~18 months later by Google (that should demonstrate the business salivation level). The real trick wasn’t just a website that played videos; it was the ingest-normalize-transcode-fanout pipeline at internet scale:

- Ingest anything: camera dumps, oddball containers, questionable frame rates, interlaced messes, you name it.

- Normalize to an internal mezzanine that you could actually work with.

- Transcode that mezzanine to multiple resolutions and bit-rates so the dialup-farmer living in a hollow in Kentucky and a broadband user both got something that didn’t suck.

- Package and serve through edge caches so “play” didn’t mean “buffer forever.”

- Sidecars (thumbs, captions, time-based metadata) got generated, too, because navigation and accessibility matter.

That model quietly trained everyone—uploaders and viewers—to expect that transcoding is the contract: you hand the platform a dumpster fire of a file (holy Sony digital camera formats); the platform hands back playable, scalable rungs that fit whatever pipe and device the viewer has. Once that expectation hardened, the rest of the industry fell in line.

The fast-forward (the original TLDR;)

Late-2000s: browser-plugin video dominates, but the codec story consolidates around more efficient DCT math (and friends) that actually looks decent at sane bit-rates.

Very late-2000s into early-2010s: adaptive bitrate over HTTP becomes the norm (think HLS/DASH). That move killed a ton of bespoke streaming weirdness: now it’s just segments over HTTP, pick the right rung, switch on the fly, don’t stall. Mobile shows up in force 2008-2010ish (ie: iPhone, Android), which makes laddered transcodes non-negotiable. Every serious service ends up with the same playbook: validate → inspect → normalize → transcode to rungs → package → distribute → monitor QoE → repeat. The names differ; the pipeline doesn’t.

Why any of this mattered (and still does)

Transcoding took fragile, time-rotting, analog-born content and made it portable across devices, networks, and years. It turned “this exact file, on this exact player, or nothing” into “whatever you’ve got, hit play.” Back when I pointed a WinTV at a wavy RF feed and captured every flaw in perfect digital clarity, it felt like magic. It still is—just industrialized. Under the covers, the job never changed: take chaos in, emit legible layers out.

And that’s the story, fast-forwarded ⏩ (mail tapes → batch encode → early streams → broadband + plugins). YouTube normalizes the ingest/ABR mindset, HTTP-based adaptive takes over. Fewer names, more pipes. The hero all along was transcoding.